VATICAN CITY — From 2002 to 2007, Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi wrote a daily column in the Italian Catholic daily Avvenire.

The column, called "Mattutino" or "morning prayer," offered a short thought for the day, and was often accompanied by a quote drawn from an array of authors. It ranged from the Psalms to obscure contemporary poets, from Christian writers to contemporary novelists and philosophers.

It was through the "Mattutinos" that most Italian Catholics first came to know Ravasi, then the director of an historic library in Milan, and discovered his blend of encyclopedic interests and knack for finding a spiritual "opening" even in the most un-Christian writers.

The fame as a moderate liberal he enjoyed within some Catholic circles could have scuppered his chances for a Vatican career, but Pope Benedict XVI came to appreciate Ravasi.

In 2007, he appointed him head of the Vatican department for culture, with the task of reopening the dialogue between the Catholic Church and contemporary secularized culture.

Ravasi accepted the challenge with his characteristic verve.

He pushed for the Vatican to have its own pavilion at the "Biennale," one of the world’s leading arts festivals, held every two years in Venice.

Then, in 2010, Ravasi, 70, launched the "Courtyard of the Gentiles" a high-profile initiative aimed at rekindling the Catholic Church’s intellectual dialogue with nonbelievers.

Perhaps surprisingly, Ravasi’s initiative enjoyed Benedict’s full support, despite grumbles from conservatives who complained that the church should call nonbelievers to convert rather than engage in debate with them.

Since its launch, the "Courtyard" has organized events in bastions of secularized culture such as Paris and Stockholm.

And Ravasi has continued to display his ecumenical interests. His speeches are peppered with quotes from sources as diverse as Herman Hesse, the Qoelet, Blaise Pascal and Friedrich Nietzsche.

In some ways, the up-and-coming cardinal is a human Internet. The mention of a topic — be it "hope" or "stem cells" — automatically brings to his mind dozens of appropriate citations, according to those who work with him. "I don’t need Google," he once told his colleagues.

As his days are now full with official engagements for his Vatican office, Ravasi does most of his reading at night.

"The worst thing you can do to him is invite him for dinner," said one of his co-workers, who asked for anonymity in order to speak candidly about his colleague. "Those are the hours he reserves for reading and writing his speeches."

Ravasi recently widened his effort to reach out to contemporary culture, moving from the rarefied world of intellectual debate to the raucous arena of pop culture.

In January, he confessed he had listened to the late British singer Amy Winehouse in an effort to understand young people’s language and feelings. "A quest for meaning emerges even from her distraught music and lyrics," he said.

But this affable scholar, whose first claim to intellectual fame came through his commentary on the Psalms, was also an early adopter of social media among the College of Cardinals.

In 2011 he opened a Twitter account and has been tweeting regularly ever since.

But co-workers say that Ravasi doesn’t use computers and writes everything in his ornate calligraphy. His tweets are handwritten and then typed by one of his collaborators.

A regular contributor to many of the main newspapers, Ravasi is a popular figure in Italy, and his popularity, together with his capacity to engage with the world that lies outside church walls, has propelled him into many lists of "papabili," or potential popes.

One factor against him: Ravasi has never led a large diocese, something that in the past decades has become a key prerequisite for the papacy in today’s world.

Yet, as the pope’s appointed preacher at a Vatican retreat the whole Roman Curia has been attending since Sunday (Feb. 17), Ravasi has found himself in the spotlight in the wake of Benedict’s unexpected announcement of his resignation.

And it was Benedict’s homily at Pope John Paul II’s funeral in 2005 that impressed many cardinals, and may have led to his own election to the pontificate.

By Alessandro Speciale, Religion News Service

Vatican City, 23 February 2013 (VIS) – Benedict XVI, in an apostolic letter, thanked Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, president of the Pontifical Council for Culture, for his preaching during the Lenten retreat.

Huffington Post on Cardinal Ravasi

Then, in 2010, Ravasi, 70, launched the "Courtyard of the Gentiles" a high-profile initiative aimed at rekindling the Catholic Church’s intellectual dialogue with nonbelievers.

Perhaps surprisingly, Ravasi’s initiative enjoyed Benedict’s full support, despite grumbles from conservatives who complained that the church should call nonbelievers to convert rather than engage in debate with them.

Since its launch, the "Courtyard" has organized events in bastions of secularized culture such as Paris and Stockholm.

And Ravasi has continued to display his ecumenical interests. His speeches are peppered with quotes from sources as diverse as Herman Hesse, the Qoelet, Blaise Pascal and Friedrich Nietzsche.

In some ways, the up-and-coming cardinal is a human Internet. The mention of a topic — be it "hope" or "stem cells" — automatically brings to his mind dozens of appropriate citations, according to those who work with him. "I don’t need Google," he once told his colleagues.

As his days are now full with official engagements for his Vatican office, Ravasi does most of his reading at night.

"The worst thing you can do to him is invite him for dinner," said one of his co-workers, who asked for anonymity in order to speak candidly about his colleague. "Those are the hours he reserves for reading and writing his speeches."

Ravasi recently widened his effort to reach out to contemporary culture, moving from the rarefied world of intellectual debate to the raucous arena of pop culture.

In January, he confessed he had listened to the late British singer Amy Winehouse in an effort to understand young people’s language and feelings. "A quest for meaning emerges even from her distraught music and lyrics," he said.

But this affable scholar, whose first claim to intellectual fame came through his commentary on the Psalms, was also an early adopter of social media among the College of Cardinals.

In 2011 he opened a Twitter account and has been tweeting regularly ever since.

But co-workers say that Ravasi doesn’t use computers and writes everything in his ornate calligraphy. His tweets are handwritten and then typed by one of his collaborators.

A regular contributor to many of the main newspapers, Ravasi is a popular figure in Italy, and his popularity, together with his capacity to engage with the world that lies outside church walls, has propelled him into many lists of "papabili," or potential popes.

One factor against him: Ravasi has never led a large diocese, something that in the past decades has become a key prerequisite for the papacy in today’s world.

Yet, as the pope’s appointed preacher at a Vatican retreat the whole Roman Curia has been attending since Sunday (Feb. 17), Ravasi has found himself in the spotlight in the wake of Benedict’s unexpected announcement of his resignation.

And it was Benedict’s homily at Pope John Paul II’s funeral in 2005 that impressed many cardinals, and may have led to his own election to the pontificate.

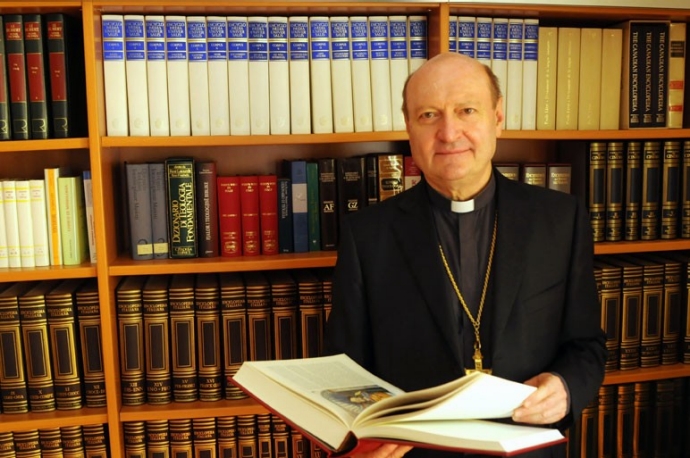

His Eminence Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi

http://www.cultura.va/content/cultura/en/organico/cardinale-presidente.html

Cardinal, President of the Pontifical Council for Culture and of the Pontifical Commission of Sacred Archaeology.

Born in 1942 at Merate (Lecco, Italy), he is an expert on the bible and biblical languages, he was Prefect of the Biblioteca-Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan and taught Old Testament Exegesis at the Theological Faculty of Northern Italy.

He has some 150 volumes published mainly on biblical topics: editions on the Psalms and the Book of Job, the Song of Songs and Ecclesiasticus. He has also earned popular fame for his writings Breve storia dell’anima (Mondadori, 2003), Le sorgenti di Dio (San Paolo, 2005), Ritorno alle virtù (Mondadori, 2005), Le porte del peccato (Mondadori, 2007), 500 curiosità della fede (Mondadori, 2009), Questioni di fede (Mondadori 2010) and Le Parole del mattino (Mondadori 2011).

Cardinal Ravasi collaborates with newspapers – for fifteen years he wrote for the daily paper Avvenire and currently writes for L’Osservatore Romano and Il Sole 24 Ore – and has his own television activity with the Sunday programme Le frontiere dello Spirito on the Italian mainstream Canale 5.

In 2007 the University of Urbino gave him the Laurea h. c. in Anthropology and Epistemology of Religions. And in 2010 he was enrolled as an honourary member of the Accademia delle Belle Arti di Brera and given at the same time the Honoris Causa of the Diploma di Secondo Livello in Comunicazione e Didattica dell’Arte.